I’ve been laid low with a bout of flu this week. I’ve been too sick to work, too sick to eat, too sick to watch trashy TV, and too sick even to write. Curiously, though, I haven’t felt too sick to read, despite my pounding head and watering eyes.

Of course, there’s a sense in which this is entirely understandable. When a bad case of the flu hits you, the best thing you can do is crawl into bed; and how better to while away long bedridden days than with a good book? Not just any book, of course. In my shivering, joint-aching, thermometer-busting misery, I wanted an old friend by my side: a well-known, well-loved old friend who would know just how to soothe me.

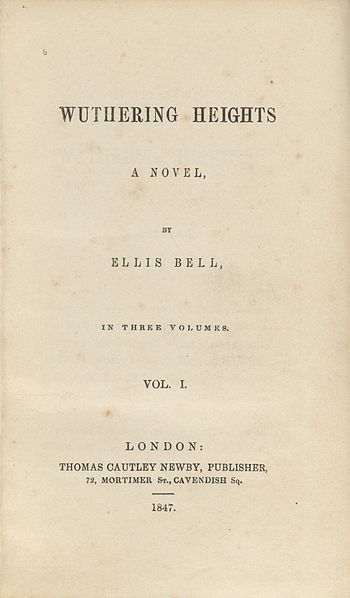

I chose Wuthering Heights.

At this point, I feel that I should make a rather sheepish confession. When I first read Wuthering Heights, as a teenager, I didn’t like it very much. I admired Emily Brontë’s artistry and narrative skill, of course, and was impressed by the sheer power that the novel evoked. However, Wuthering Heights struck me as being a cruel, brutal, sadistic novel. The characters were repulsive. Catherine was vain and vindictive, and Heathcliff was a thug; I didn’t understand what they saw in each other, but as far as I was concerned they were welcome to each other.

I was perplexed, perhaps. Everything I had ever heard about Wuthering Heights suggested that it was a love story, a romance; yet now that I was actually reading it, it seemed more like a hate story. It was a story about obsession, misanthropy, isolation, revenge, and the perpetuation of child abuse from generation to generation. I felt slightly deceived, perhaps. I wasn’t sure exactly what I’d been expecting, but it certainly wasn’t this.

Still – and this is often the mark of a really good book, to my mind – Wuthering Heights stayed with me. It lingered in my mind like a faint but insistent echo. The discomfort it had provoked in me, far from diminishing its influence, actually seemed to increase it.

A few years later, I picked up Wuthering Heights again. This time, I found, I was able to see it in a different light.

I had indeed been deceived that first time round – not by Emily Brontë, but by everyone who had talked of Wuthering Heights as being solely, or primarily, a love story. Barbara Cartland wrote love stories. What Emily Brontë wrote was closer to The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

An odd comparison? On the surface, perhaps. Yet I suspect that, in their different ways, Emily Brontë and Robert Louis Stevenson were both attempting to do the same sort of thing: to explore and analyse the different strands of the human personality, in a way that bypassed traditional moral judgements and seemed closer to modern psychoanalysis. Both sought to understand the different shades of the human character by means of a study of duality, and both also attempted to resolve the contradictions they found.

In Wuthering Heights, the tone is set by Brontë’s unconventional narrative form. A story within a story, the account is commenced by Lockwood and then handed over for the most part to the kindly housekeeper Nelly Dean. No one person has absolute access to the truth, in Wuthering Heights; the story comes to us by degrees, and from varying viewpoints.

This is appropriate, for Wuthering Heights is a novel of differing perspectives, and of contrasts. Heathcliff’s fiery, obsessive desire is compared to Edgar Linton’s more controlled and inhibited courtship. Catherine’s desperate, passionate need for Heathcliff is quite distinct from her more conventional affection for the man she chooses to marry. The wildness and austerity of Wuthering Heights itself forms a clear contrast to the respectability and gentility of Thrushcross Grange and the Linton family. Throughout the novel, these distinct elements seem to be in a state of almost constant war; they clash, oppose each other, and give rise to almost unbearable tension between the characters. They seem also to be representative of the different facets of human nature: the rational and the irrational, the conventional and the unconventional, the personal and the social. We are all in part the violent, selfish Heathcliff, just as we are all in part Mr Hyde. We cannot argue with these different sides of our personalities; we can try to repress them, but we cannot kill them off. How can we reconcile them, and become balanced human beings?

Brontë offers no clear answers, but she does hold out the hope that we can achieve such a balancing act. At the end of the novel, when Heathcliff, Catherine and Linton are dead, when all their battles are fought and their victories and defeats counted, a delicate synthesis and resolution is achieved. The younger Cathy and Hareton find love together; the dead lie quietly in their graves, and the living go about the business of their lives just as they always have. In the famous final sentence, as Lockwood stands by the graves of Catherine, Linton and Heathcliff – all now buried together, in a symbolic realisation of the harmony that eluded them in life – he says:

“I lingered round them, under that benign sky; watched the moths fluttering among the heath, and hare-bells; listened to the soft wind breathing through the grass; and wondered how any one could ever imagine unquiet slumbers, for the sleepers in that quiet earth.”

Thus this most stormy and passionate of novels ends on a soft, and softly optimistic note: a synthesis can be achieved, peace can be found, and opposites can be reconciled. The novel that had depressed and disturbed me when I was a teenager was both provocative and soothing, both more unconventional and at heart kinder than I had imagined.

So thank you, Miss Brontë: thank you for sitting by my bedside while I was ill, and telling me your stories. Thank you for giving me imaginative access to a time and place unknown to me. And thank you, above all, for writing a novel so ahead of its time that even now, over 150 years later, it can still be misunderstood.